Saturday, 20th April 2024 at Theatre @41 Monkgate, York.

⭐️⭐️⭐️

Five women have their stories forever intertwined with Jack the Ripper: Mary Ann ’Polly’ Nichols, ‘Dark Annie’ Chapman, Elizabeth ‘Long Liz’ Stride, Catherine Eddows and Mary Jane Kelly. In The Roses of Whitechapel, writers Jonathan Kaufman and Martin Stiff give the murdered women a platform to tell their own stories.

The play takes us to 1888 through costuming and dated expressions in dialogue but entertains no fuss with set or staging. In this imagining, the five are known to one another and meet to tell tales of their days and to enjoy some name calling of a blue nature (although there is no evidence to suggest that the women did ever meet). In turn, these women tell us a little about themselves, or else we learn about them by eavesdropping on them. They’re all clearly of the streets in one way or another, down on their luck and struggling to make ends meet – but not necessarily as prostitutes as was all too readily assumed at the time.

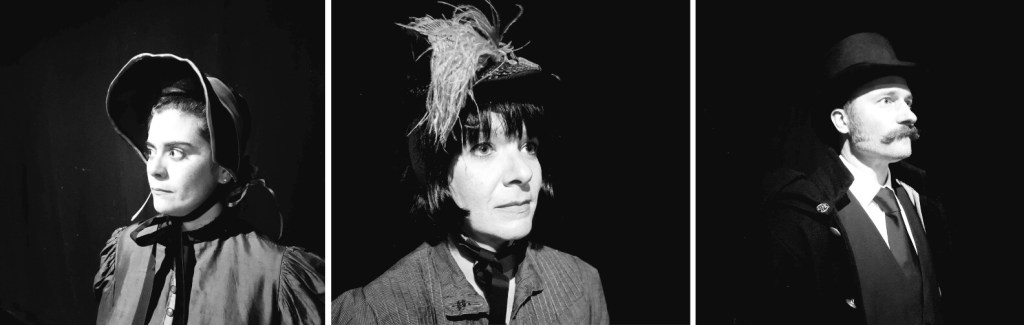

Gradually, each woman meets her fate when the Ripper (a brilliantly ominous and impactful Alexander King) appears to gloat over his actions, and the other women recite the harrowing post mortem exam findings. There are thankfully no attempts to portray any level of violence or harm, but those recitations are enough to curdle the stomach all by themselves.

What’s interesting in this approach is that as each woman dies, she becomes part of a ghostly chorus, looking on and speaking to the next victim with pleading words, knowing full well the next victim cannot heed the warnings. It’s a powerful display of helplessness which, along with the defiant closing words, does justice to the play’s intention to humanise the women who so quickly lost their identity through the notorious nature of their deaths. Also engaging in approach is that our cast take on additional peripheral roles, channeling the local journalists or police inspectors, and those departures to press and police offer excellent snapshots of callous disregard and frustrating ineptitude.

The cast are a great collective too, working together seamlessly to uncover lesser known information about their characters and offering snapshots of lives lived rather than simply lives lost. Samantha Hindman (who also directs) gives ’Polly’ Nichols a great edginess as a woman who recognises her lot in life and doesn’t have much patience for those with their heads in the clouds – and Hindman also takes a great turn as the officious constable.

Sonia Di Lorenzo’s Catherine Eddows is all volume and confidence (and not without wit) but Helen Lewis is the most bolshy and bawdy of all as ‘Dark Annie’ Chapman, a big character well aware of her own struggles but always quick to a witticism. Elizabeth ‘Long Liz’ Stride is a quieter figure in the hands of Hannah Rebecca Thornton, who tells us of her children with starry eyes but isn’t without a defensive edge of her own, too. Amy Lodge’s Mary Jane Kelly cuts perhaps the most sympathetic figure, with her gentle characterisation (again, not without an edge) transforming into a dramatic display of devastation as her autopsy report is mercilessly read aloud.

In terms of seeking to give a voice to the victims so often overshadowed by the mystery of the killer himself, the play meets with mixed results. The victims certainly lead the narrative, but Jack is also given impactful stage time and is allowed his moments to gloat and stare – useful for progressing the plot, but somehow contradicting the idea of giving all weight to the women themselves. Equally, when one woman begs to skip the autopsy reading, and has the plea accepted, it feels like a turning point; the women will finish the story as individuals, not mutilated victims. But the final victim is then accosted with her report, and in greater detail than the others, so we take a step backwards and return to the morbid emphasis on what happened to the bodies of these women rather than their lives.

Finally, when Jack tells us that the “cycle of violence” was (and is) pleasingly continued by crime scene images and key documents being printed and re-printed – thus securing his legacy – he exposes the true weight of that decision to return to the post mortem readings: if the piece were truly to have the women take back their story, there would surely be more dignity and less time being accosted with the gruesome details so aggressively. It all certainly makes for powerful and unsettling theatre, and it’s performed very well here by The Penny Magpie Theatre Company; I’m just not sure Kaufman and Stiff’s play meets expectations of empowering those left without a voice for so long.

The Roses of Whitechapel has completed its run at Theatre 41, but you can check out the theatre’s other listings here.